Aquifer issues

The range of views held by the agenda-setting elites of both parties is, on some issues, much narrower than the range of views held by the general population. Consequently, large shares of the electorate are left holding political views with no room for expression in the usual, constrained arena of debate. If the proportion of eligible voters holding these unrepresented views grows sufficiently large, they become a kind of latent, or potential, energy—a pool of support which can give an unexpected boost to an unconventional politician who succeeds in tapping them. For now, I’m calling these “aquifer issues” because they remain silent and unused until an enterprising public figure taps into them.

Contested issues

To appreciate how aquifer issues lie outside our traditional models of politics, let’s consider the median voter theorem—a staple of two-party systems like the one we have in America. Imagine 100 people who’ve decided to divide up $100 by majority vote. If these people act out of naked self-interest, a minimal winning coalition of 51 voters will form, splitting the money evenly between all 51 of them. If the coalition was any bigger, they would each get less. Obviously, this is a very crude analogy to actual politics, but the basic insight is useful. Majorities are often constrained in size because the bigger the majority, the more each constituent group has to compromise.

Abortion is a good example of how this works. Almost everyone has an opinion about it. Opinions range from “abortion for anyone for any reason at any time”, to “no abortions for anyone without exception.” Most people fall somewhere in between. Neither party’s national elite agenda setters sit at either extreme, but Democrats and Republicans clearly differ from each other in ways that are well-understood by voters. Each party strives to find the smallest durable majority in support of its basic position. It needs a majority to get what it wants, but further expansion of the majority risks introducing untenable compromises among coalition members.

This is what the model suggests, at least. I think it’s a reasonably accurate simplification of abortion politics in America. Democrats and Republicans split the vote almost evenly, with differentiated attitudes toward abortion featuring prominently among their respective voters. When a contested issue like abortion becomes sufficiently salient to ordinary voters, politicians can use it as a wedge issue to hold onto voters who might agree with their opponent on other, less personally important topics.

Aquifers

This idea that parties more-or-less self-consciously position themselves on issues in a bid to attract a minimal winning coalition fails to explain aquifer issues. Sometimes the two parties basically present a unified face on a particular subject. They may well posture as if they disagreed, but their differences are insignificant compared to the range of preferences held by the general population. They offer a choice between dark-gray and medium-gray when many of the voters actually want green.

Whether by intent or accident I do not know, but Donald Trump benefited from at least three aquifer issues in his 2016 election—immigration restrictionism, foreign policy isolationism, and white resentment.

Immigration

Compared to the Trump era, previous immigration debates look tame. Clinton signed the IIRIRA, which passed with bipartisan support. Republicans and Democrats during the Bush and Obama administrations argued over immigration, but their differences now seem relatively small. Both agreed that undocumented immigration was bad; they just disputed whether to target the individuals or employers. Both agreed Dreamers should be given legal status; they disagreed on the timeline. Neither party suggested reducing the number of immigrant or refugee visas granted.

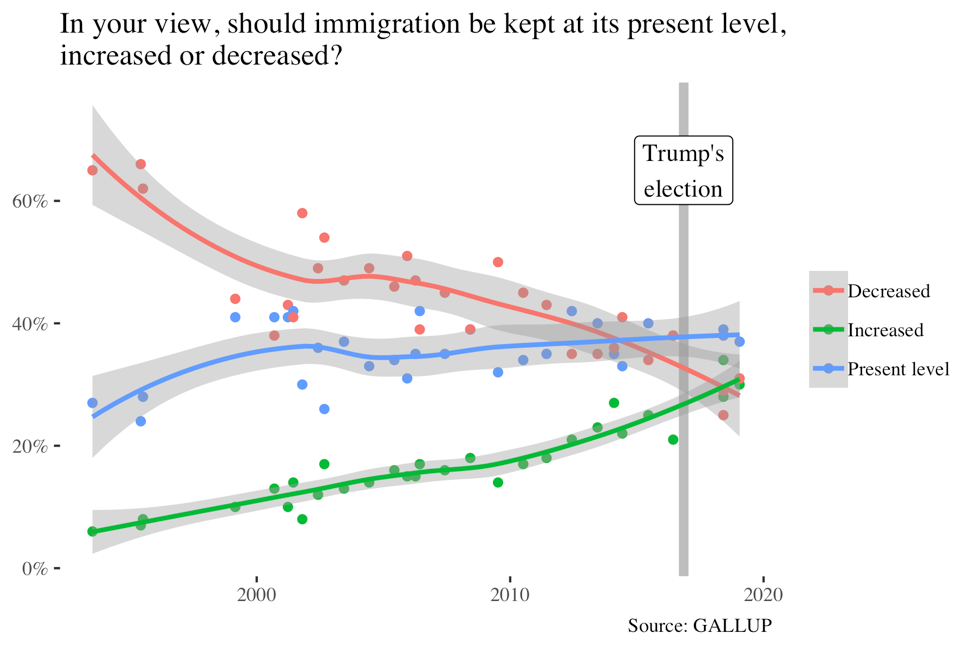

This relative agreement obscured widespread general opposition to immigration among the public at large. Throughout the 1990s, over 60% of Americans thought immigration levels should be decreased. Pat Buchanan’s campaign for the Republican nomination in 1996 sought to capitalize on this sentiment, but the party managed to suppress it in favor of their preferred candidate Bob Dole. Americans became considerably more favorable toward immigration over the following two decades, but in 2016 38% still thought total immigration should be decreased—the same number as thought it should be increased. Trump was the only Republican candidate to make restricting legal immigration a campaign priority. In fact, for the substantial portion of the American population supporting this position, this was their first opportunity to vote for a major party nominee who agreed with them in decades.

Isolationism

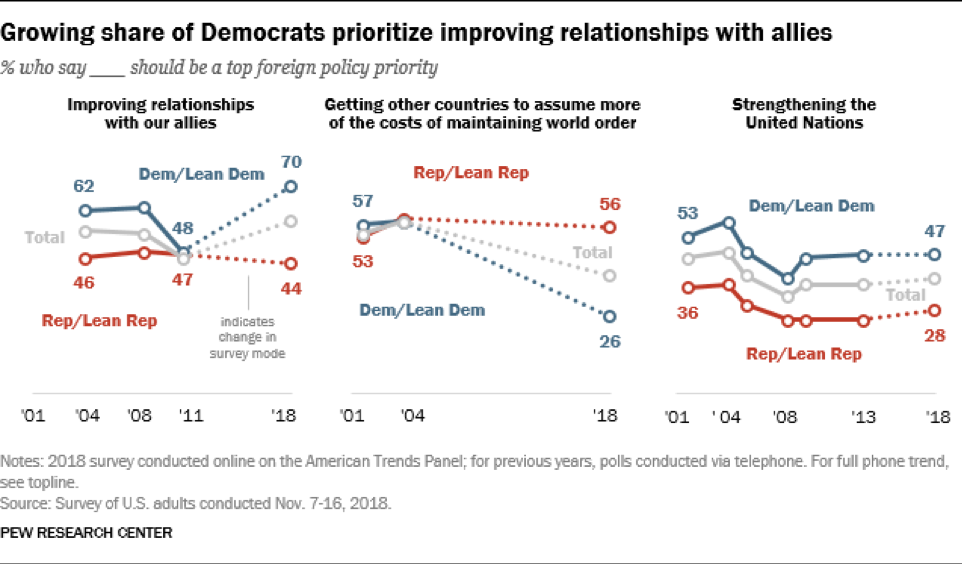

Prior to Trump, isolationist foreign policy perspectives carried little weight with either party. If anything, the Republican party may have been more committed to military relationships with our allies. This bipartisan elite consensus on foreign policy was not shared by the entire electorate. In 2004, for instance, equivalent majorities (57%) of Democrats, Independents, and Republicans said “getting other countries to assume more of the costs of maintaining world order” should be a “top foreign policy priority.” Likewise, there was no difference between the parties regarding the importance of “improving relationships with our allies”—just under half thought this was a top priority.

I think Ron Paul’s surprisingly strong performance in the 2012 Republican primary (3rd place with 11% of the vote) likely reflects the latent appeal of isolationism. His isolationist views were certainly more popular than the libertarian blend of economic conservatism and social liberalism his campaign otherwise represented.

Racial Resentment

The abundance of Donald Trump’s racist campaign appeals need no recounting here. Many critics have argued that he only made explicit the kinds of racist dog whistles Republican politicians had been using for years. While the existence of the so-called “Southern Strategy” (or “suburban strategy,” in another formulation) is indisputable, it is also true that Trump’s appeals to white resentment ginned up support in a different way than McCain in 2008 or even Romney in 2012. I say “even” not because Romney made more explicitly racist arguments than McCain, but because by 2012 less-educated whites were beginning to make a stronger connection between the Democratic Party and liberal racial policies.

“For many years, whites with less formal education had not mapped their views about race onto their broader political views. Because they tended to follow politics less closely, they had not fully learned or internalized the long-standing divisions between the Democratic and Republican Parties on civil rights and other issues related to race. But once Obama was in office, whites with less formal education became better able to connect racial issues with partisan politics. There was a large increase in the proportion of non-college-educated whites who knew that the Democratic Party was more supportive of liberal racial policies than was the Republican Party.”1

With his overt appeals to white resentment, Trump at least accelerated this trend. An analysis of multiple panel surveys reveals that, “attitudes about race and ethnicity were more strongly related to vote choice in 2016 than they were in 2008 and 2012—even after accounting for people’s partisanship and their overall political ideology on the left-right scale.”2 The same effect held for views toward other minority groups like illegal immigrants and Muslims.

Barack Obama’s presidency made more clear the connection between racial progressivism and the Democratic Party to less-informed voters. Trump’s campaign made the connection between racial resentment and the Republican Party explicit.

A short shelf life

Aquifer issues cease to be aquifer issues as soon as they are used. Now that Donald Trump has activated the three issues I discussed above, he owns them. As a result they’ve become traditionally partisan issues. Democrats are more supportive of immigration than ever before, more opposed to isolationism, and dramatically more likely to say more policy changes are needed to combat racial discrimination.

What are other aquifer issues?

Most public pollsters spend their time asking people how they feel about their politicians and the policies they are proposing. The range of responses are constrained by the options presented by the politicians themselves. As a result, it’s hard to say what untapped reservoirs of public support remain. Here are a few possibilities:

- anti-vaxxers

- jobs guarantees

- water fluoridation (historical example)