How Much of the Republican Assembly Victory was Thanks to Incumbency?

Democratic state assembly candidates were less popular than either Kamala Harris or Tammy Baldwin this past November. Of the 99 Assembly seats, Baldwin won 50, Harris 49, and actual Democratic candidates 45.

This, in itself, was not a surprise. We know that incumbents usually enjoy a slight popularity boost, and there are more incumbent Republicans than Democrats. The 2024 assembly races featured 57 incumbent Republicans and 27 Democrats in contested races.

But does incumbency advantage explain all of the Republican assembly majority? A careful accounting of the evidence suggests not.

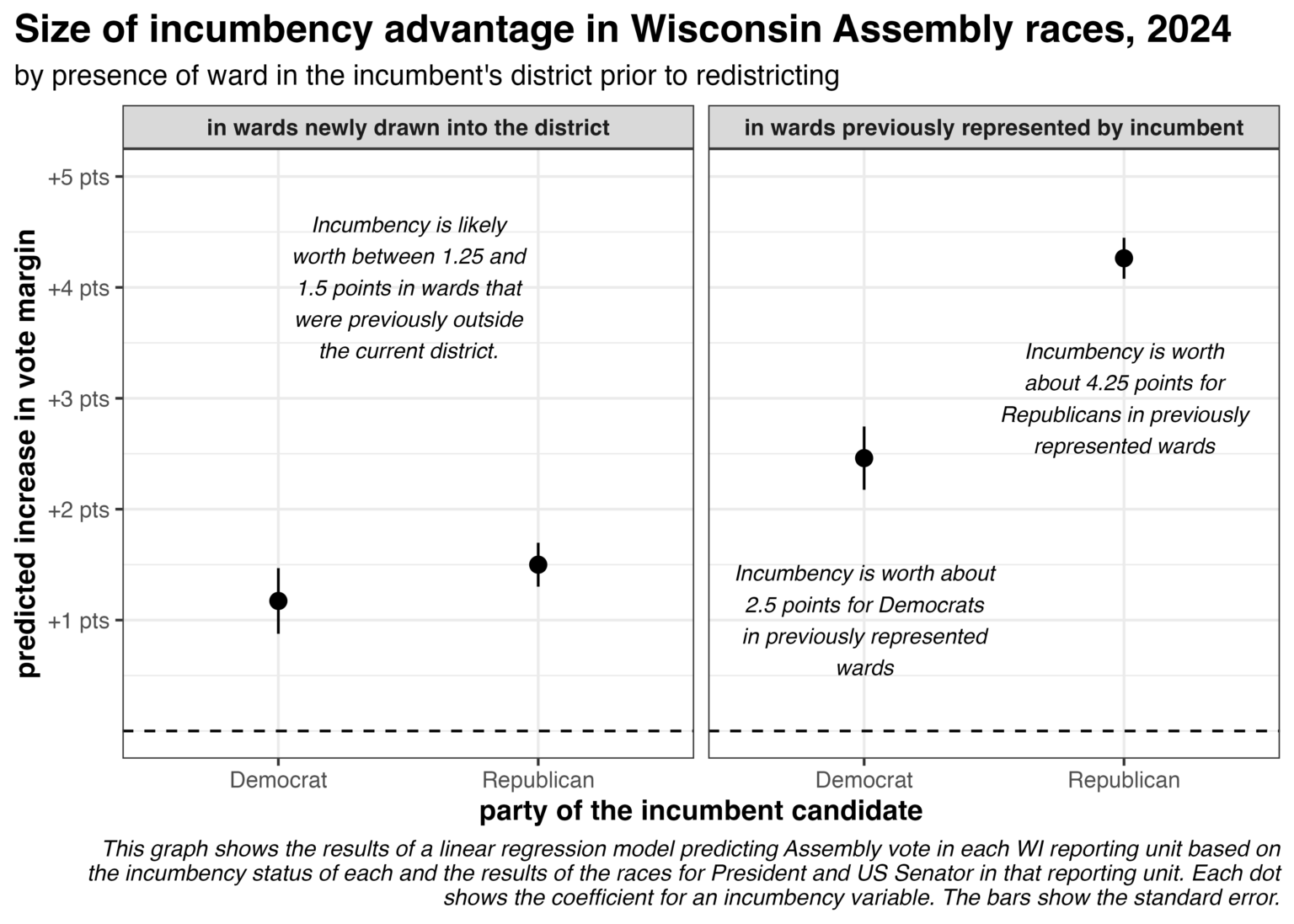

Measuring two kinds of incumbency advantage

The 2024 election is the first to use maps drawn by Democratic Governor Tony Evers, rather than previous maps drawn by Republican legislators. When the new state assembly maps were first released, I estimated that the 2022 assembly elections would’ve resulted in 46 Democratic seats, had the election taken place under the new maps. This, despite the fact that Governor Evers won reelection in that year by 3 percentage points.

Incumbency advantage comes from at least two sources. In places where they’ve run before, incumbents likely enjoy higher name recognition than an opponent. Apart from that, they might still run better campaigns simply by dint of greater experience.

Redistricting offers a unique opportunity to decompose these two sources of incumbent strength. Most incumbents ran in new districts which only partially overlapped with their previous seat. The benefits of name recognition should primarily exist just in those overlapping areas, while the benefits of experience should appear everywhere.

To measure this, I created a statistical model predicting the assembly vote in each ward based on the following variables:

Vote for President

Vote for US Senator

Dummy variables for:

If the Republican candidate previously represented this ward

If the Republican candidate previously represented other wards

If the Democratic candidate previously represented this ward

If the Democratic candidate previously represented other wardsI dropped the small number of wards which were split between previous districts from the analysis. As you might expect, the terms for the two statewide races explain almost all the variation in vote between individual wards. But the coefficients for incumbency status are all strongly significant as well. Here are those results.

Imagine a hypothetical 50/50 ward in an assembly district perfectly divided between the parties. If either the Democratic or Republican candidate were an incumbent who had not previously represented this district, we would expect them to win by a bit more than a point. The coefficient for Republican incumbents is slightly higher than for Democrats, but the difference is not statistically significant.

Now consider another hypothetical 50/50 ward which was previously represented by the same incumbent running for reelection. The model predicts an advantage to a Democratic incumbent of about 2.5 points, while for a Republican it is about 4.25 points.

In other words, Democratic and Republican assembly candidates appeared to benefit equally from incumbency when running in wards new to their districts, but Republicans benefited more from name recognition than Democratic incumbents.

Why is this? I don’t know. In 2022, there was no difference in incumbency advantage between Democrats and Republicans.

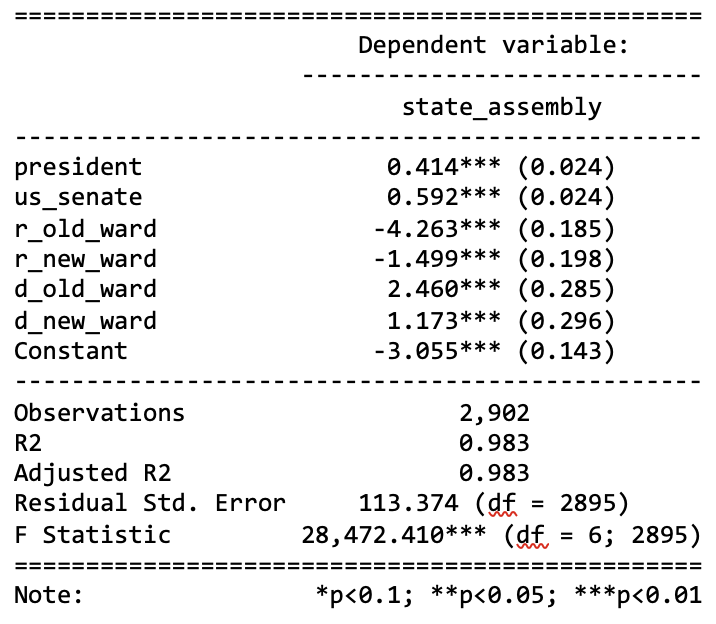

Here are the full results of the model. All values are expressed as margin points, or the Democratic percent of the two-party vote minus the Republican percent. The intercept of the model is a ward with no assembly incumbent and a tie in both in presidential and US senate races.

In this scenario, the model predicts a 3.1-point victory for the Republican assembly candidate. Holding every other variable constant, a 1-point increase in support for Harris predicts a 0.4-point increase in support for the assembly Democratic, and a 1-point increase support for Baldwin predicts a 0.6-point increase in support for the local Democrat.

In plain English, the model shows that Republican assembly candidates did about 3 points better than Trump or Hovde, even when they weren’t incumbents. Incumbents running in new wards improved on this by a bit more than 1 point, whether Democratic or Republican. When incumbents ran in wards they had previously represented, Republicans did about 4.3 points better than otherwise expected, compared to just 2.5 points better for Democrats.

The vote for president and US senate are both extremely correlated with the vote for state assembly. That said, the vote for US senate is a bit more predictive.

Where incumbency made the biggest difference

If no incumbents had run, my model suggests that several races might have ended differently. Incumbency advantage probably saved two or three Republicans and one Democrat. So, in its absence, Democrats likely would’ve netted one or two extra Assembly seats, still less than a majority.

The seats where incumbency likely made the biggest difference are as follows:

The 21st, in the southern Milwaukee County suburbs, where incumbent Republican Jessie Rodriguez narrowly defeated a Democratic challenger. Rodriguez was first elected in 2013.

The 61st, in the southwestern Milwaukee County suburbs, where incumbent Republican Bob Donovan defeated LuAnn Bird in a rematch of his first election in 2022. Prior to serving in the Assembly, Donovan was a longtime alderman on Milwaukee’s near south side. In would not surprise me if many of his suburban constituents, like Donovan himself, also previously lived on Milwaukee’s south side.

The 51st, west of Madison in southwestern Wisconsin, where moderate Republican Todd Novak won reelection to a sixth term.

The 94th, stretching from La Crosse north along the Mississippi River, where Steve Doyle won a seventh term. This continued Doyle’s streak of winning close races in one of Wisconsin’s most competitive districts.

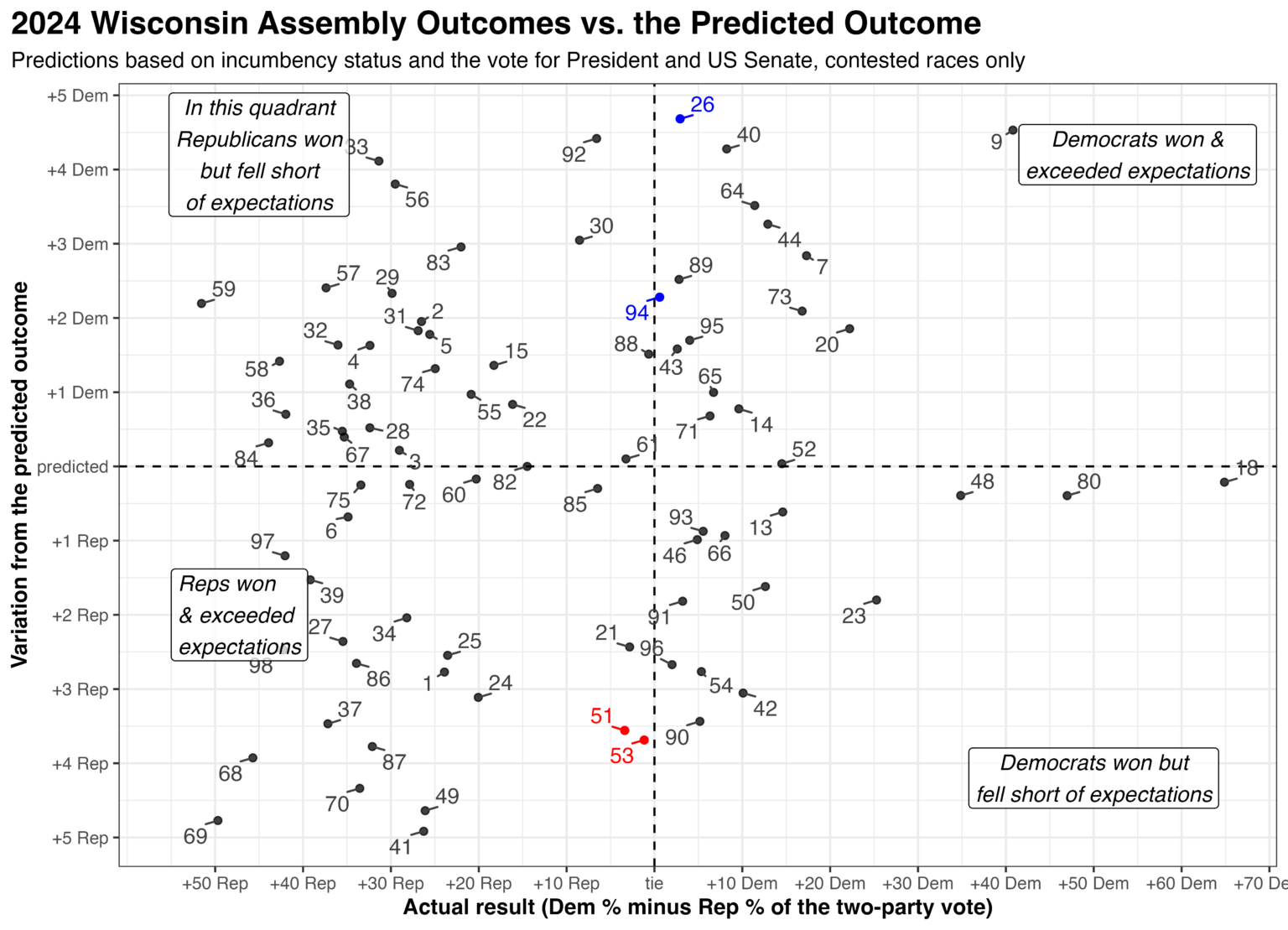

The next graph shows how well each candidate performed compared with the model’s expectations, taking into account incumbency status in each ward and the vote for president and senate.

The two seats shown in blue are seats that Democrats won despite the model predicting a Republican victory. They are the previously discussed Steve Doyle seat and the 26th district, covering the city of Sheboygan. Here, the Democrat Joe Sheehan narrowly incumbent Republican Amy Binsfield, who represented the partially overlapping 27th district. Sheehan outperformed the model’s expectations more than any other Democrat.

Republicans won the two red seats, contrary to the model’s expectations. These are Todd Novak in the previously mentioned 51st district and Dean Kaufert in the 53rd (Neenah/Menasha).

The Republican politicians who most outperformed the model’s expectations are found in the deep red 41st, 49th, 69th, and 70th districts.

Republican assembly candidates were more popular than Trump or Hovde

In 2024, Republican incumbency advantage came in two forms for assembly candidates. For one, there were just a lot more Republican incumbents running in contested races than Democrats. But Republican incumbents were also more popular than Democratic incumbents when running in wards they had previously represented. This fact is different than in 2022, and I don’t have a good explanation for it. Possibly Republican politicians did a better job than Democrats at building name recognition among the less-frequent voters who show up in presidential years.

Still, even combining the two sources of incumbency advantage only explains one or two of the 4 and 5 seats, respectively, that Trump and Hovde lost but assembly Republicans won.

About 27% of the state’s voters lived in a ward with a contested, open assembly race—where no incumbent ran. These wards were slightly more Democratic than the state as a whole. Harris won them by 1.2 points and Baldwin by 3.4. But across all these wards, the Republican candidates eked out a 0.7-point victory.

Many observers of the 2024 election have concluded that Trump was a strong candidate and Harris a weak one. That story is not entirely consistent with the evidence from Wisconsin. To an extent not explained by incumbency effects, Trump was less popular than the average Republican assembly candidate, and Harris performed better than most Democrats running for state office.