Sheboygan County’s Remotest Point

Long ago, maybe around 20,000 BC, a large chunk of ice calved off the retreating Wisconsin Glacier somewhere east of the future Lake Michigan. In 1653, Izaak Walton published the first edition of The Compleat Angler: Or the Contemplative Man’s Recreation, part how-to guide and part subtle protest of Puritan rule in Commonwealth England. And in the 1920s, the bottom fell out of America’s farm economy, largely as a result of overproduction for military consumption in World War I. All these events contributed to the current location of Sheboygan County’s remotest point, which I set out to visit on the morning of August 9, 2025.

This point, (43.8420306363191, -88.1031025847307) lies in the Sheboygan Marsh 1.4 miles from the nearest road. Maybe that doesn’t sound all that far to you, but it’s the furthest you can get from a road anywhere in Sheboygan County. Anyway, crow’s flight distance is deceiving, as you’d be hard-pressed to access the point from either of the nearest roads. Wetlands, punctuated by deep “ditches” surround it in all directions.

But for the post-war farm crash, roads would probably crisscross the whole area. The modern-day marsh took shape around 13,000 years ago when the glacial kettle lake formed by that melting ice block finally filled with sediment, forming dozens of feet of peat. A nearby limestone formation acted as a dam, keeping the marsh from simply draining off into Lake Michigan, fewer than 20 miles to the east. It took several attempts over a few decades, but local businessmen succeeded in draining the wetland by the early 1920s, after removing the limestone dam and digging drainage ditches. Their scheme to sell the resulting dry land to farmers failed when the price of farmland crashed. The drained peat fields frequently caught fire, burning as deep as three feet into the earth. At least one of the fires burned more than 1,000 acres.

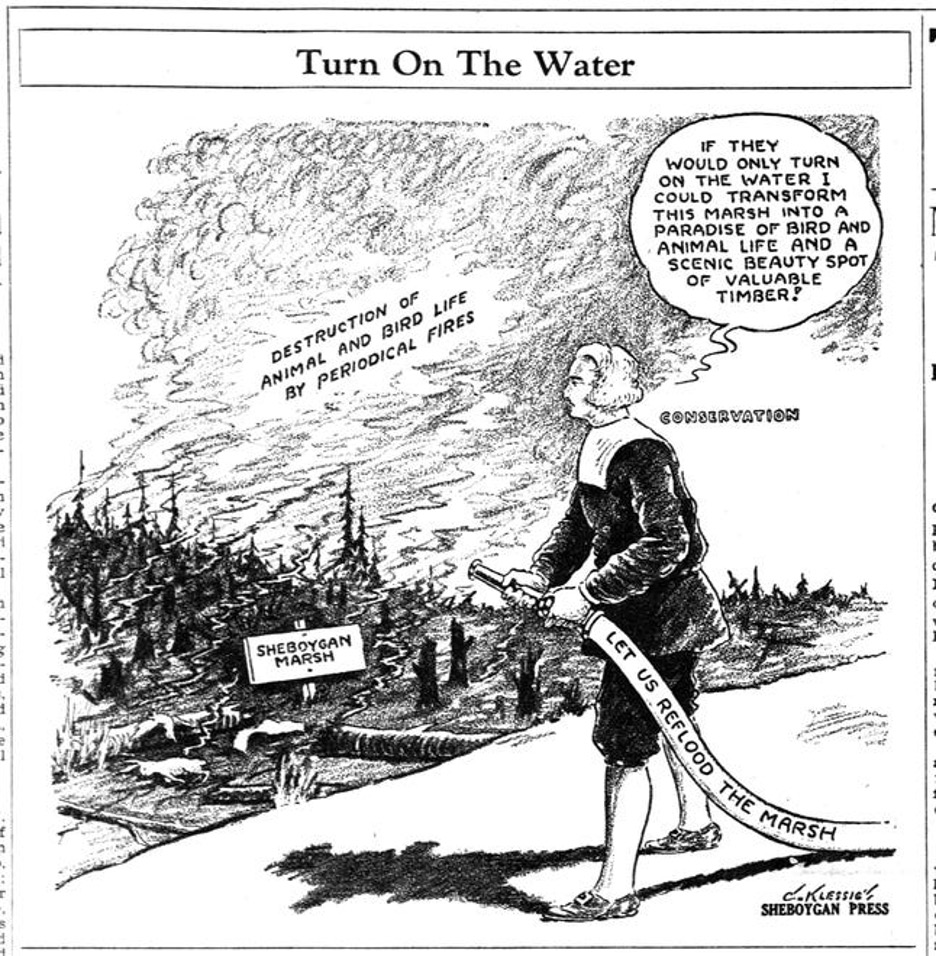

By the late 1920s, local environmentalists from the Izaak Walton League (founded in 1922) had begun agitating for restoration of the marsh. The league (America’s first mass membership environmental organization) had an influential ally in the publisher of the Sheboygan Press, Charles Broughton. Broughton printed the cartoon below in a 1931 edition of the Press. The stockinged fireman labeled “CONSERVATION” unmistakably resembles Walton.

Conservation efforts succeeded when, in 1937, the county government purchased over 6,000 acres of the land at foreclosure auction, and in 1938, the Works Progress Administration built a new dam, reflooding the marsh. Today, the county still owns most of the marsh, but (aside from a small park) it is managed by the Wisconsin DNR. Many migratory birds rely on it. Hunting is entirely prohibited in a 1,522 acre refuge at the marsh’s southern end, where no entrance for any reason is allowed during September, October, and November.

Having chosen early August for our adventure, my friend Ben and I set off into the marsh with no legal restrictions on our movements but plenty of cattail-related constraints. Much of the marsh is full of the plants, and I’m not sure what I would’ve done if the remotest point had fallen in the midst of them. Happily, our goal was a wooded area, surrounded on three sides by the winding Sheboygan River and on the fourth by the river-sized but dead straight Main Ditch.

We launched our canoe from Riverside Park in St. Cloud and waded through the shallow water under the middle arch of an old stone footbridge. That was the only bridge we passed. The entire route was about 7 miles, start-to-finish. We took out at Sheboygan Broughton Marsh County Park, following the path described by the excellent Wisconsin blog Miles Paddled. For roughly miles 2 through 6, we were far enough from the roads to avoid even the faint sounds of passing cars. Instead, we saw and heard scores of birds. To name a few: blue herons, sandhill cranes, various sandpipers, a night heron, a bald eagle.

Water levels were low for the first couple miles, and it was a relief when we could finally dip more than a few inches of our paddles into the water with each stroke. Dozens of footlong catfish appeared to be resting in the shallow water along the muddy banks. The disturbance of our passing canoe would arouse them into violent flopping as they sought deeper water. One of them struck the bottom of our canoe in its haste, giving us a jolt like striking a sunken log.

Eventually we departed the official river channel to follow the so-called Main Ditch. For me, “ditch” brings to mind a small trench with variable flow. This ditch, however, was as wide as the river and plenty deep enough for easy navigation. We made good time and soon drew level with the Remotest Point. Beaching the canoe on a shallow bank, we fought our way through several hundred feet of serrated grasses and brambles. Scat of multiple kinds of was plentiful, and I almost stepped on a decaying pile of a fur and bones. We passed no sign of any trail. I’m sure our remotest point has been visited before, but neither often nor recently.

The view from the point itself was mostly nondescript, as is usually the case with these adventures. It is surrounded by trees in a grassy floodplain. At that moment, the ground was somewhere between dry and soggy.

Back in our canoe, we continued down a series of channels until just above the site of the dam whose construction had refilled the marsh nearly 90 years ago. The moderate breeze we began the day with had become a ripping tailwind. We could tell rain was in the offing, but I had no idea how much. On the way home we drove into a “millennium storm.” Lest we needed a reminder of the importance of wetlands, parts of southeastern Wisconsin got 12 inches of rain in 24 hours.