McDonough County's dismal economic trajectory

The view from the back porch in Bardolph, IL. Photo credit: Elena Johnson.

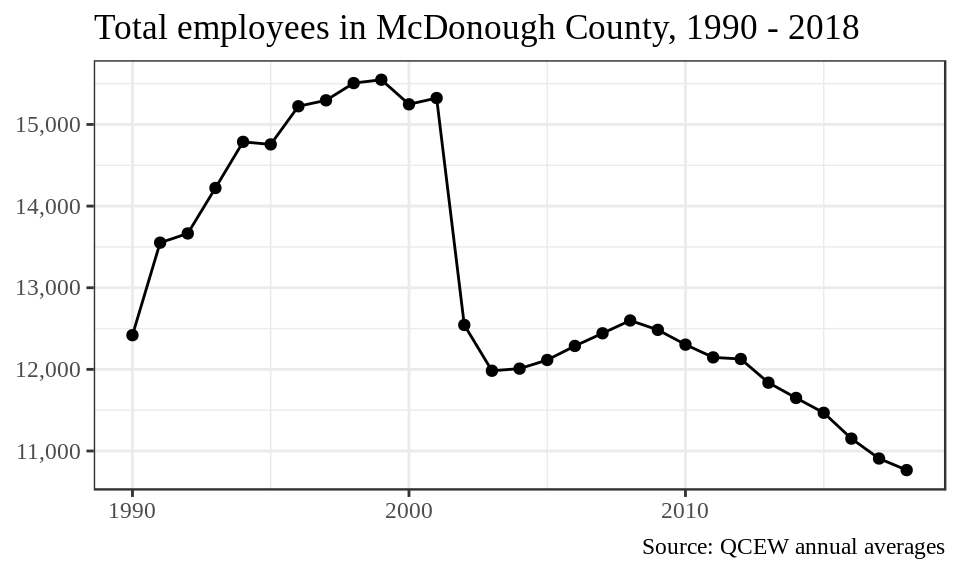

In hindsight, my family picked a bad time to move back to McDonough County. We moved to Bardolph (pop. 253) in 1997 to be near my mom’s aging parents who still ran the farm she grew up on. At the time it didn’t seem like a bad move financially either. The 1990s were good for the area. The local economy added more than 3,000 jobs over the decade–a growth rate of 25%.

Nationally, the “early 2000s recession” barely warrants a Wikipedia article. It officially lasted only 8 months. In Western Illinois, however, it was a massacre. From 2001 to 2003, the county lost more than a fifth of its jobs. Most of them have never come back. The Great Recession in 2008 ended the modest recovery and inaugurated a period of job loss which continues unabated to the present.

My dad spent the early 2000s being successively hired and laid off from the shrinking menu of factories left in business. Eventually, he saw the writing on the wall at Haeger Pottery1 and took a job at a swine slaughterhouse 40 miles away in Beardstown.2

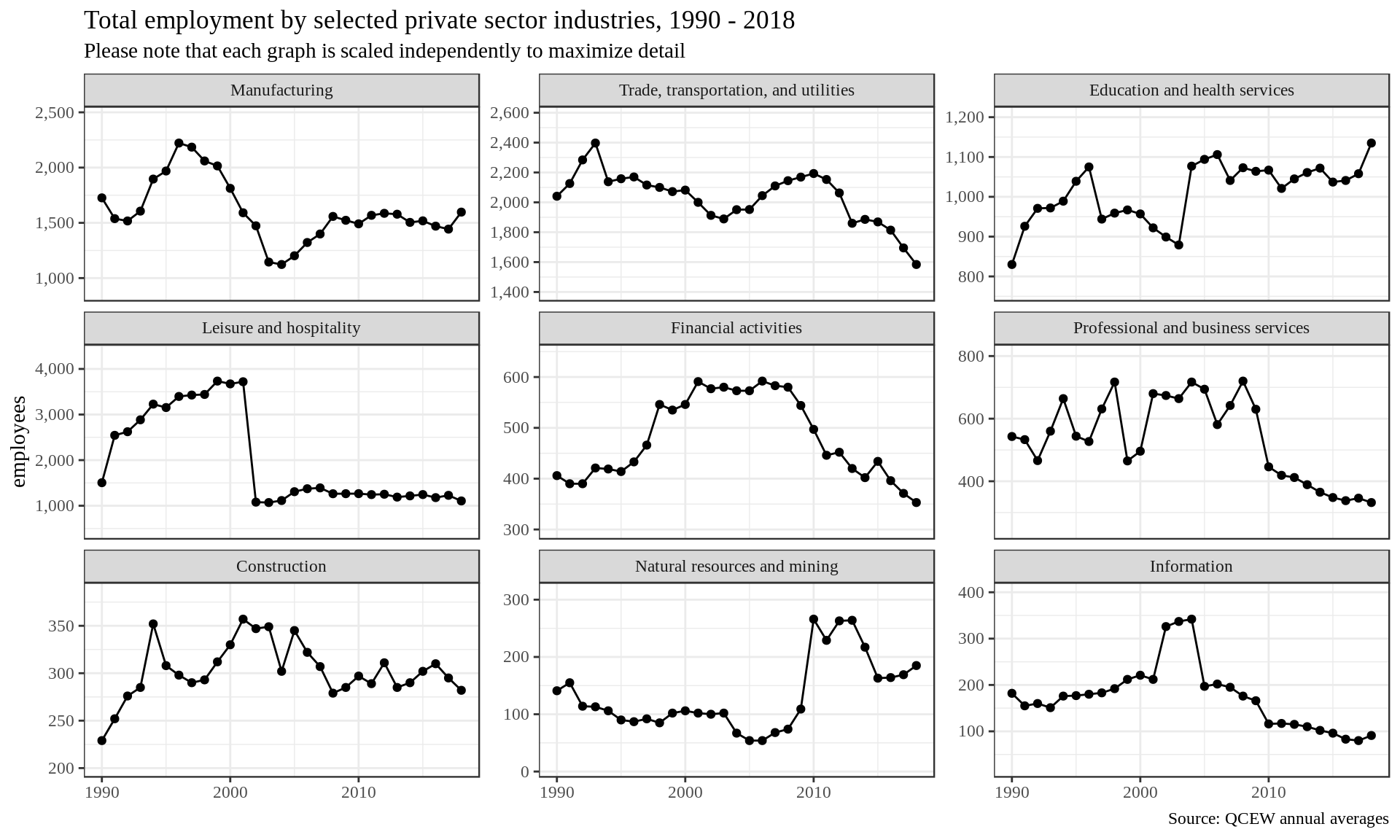

His experience was shared by many. Manufacturing, which had recovered during the ’90s, was devasted in the early 2000s. In 1999, 33 establishments employed some 2,000 factory workers. This fell almost in half to 1,100 employees by 2004. Employment has recovered a bit since then, even as the total number of employers has continued to shrink. In 2018, 21 manufacturers employed 1,600 people.

Different industries have followed varying economic trajectories over the past 30 years, but decline and stagnation unite most of them. Trade, transportation, and utilities (McDonough’s largest employer) weathered the early 2000s relatively well but declined by 26% from 2008 to 2018. Leisure and hospitality lost a shocking 70% of its jobs in just one year from 2000 to 2001. Financial activities remained strong during most of the 2000s but proved vulnerable to the Great Recession and its aftermath. This sector has contracted by 39% since 2008.

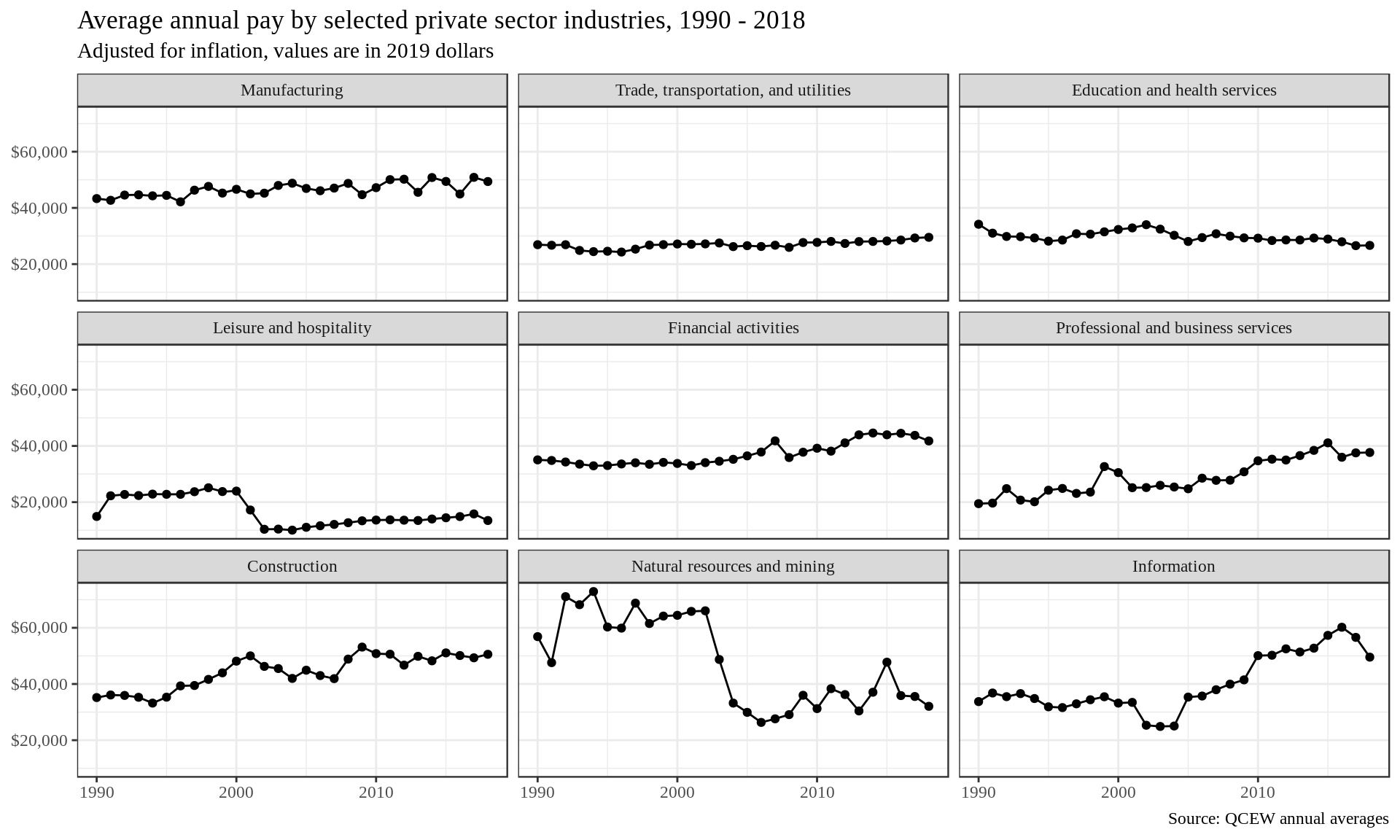

The most significant area of improvment over the last few decades is in Education and Health Services. In contrast to all other major employers, this sector has shown at least steady levels of employment throughout the most recent economic crisis. This good news is tempered, though, by the low wages these jobs pay. Average pay has risen in the shrinking industries. Presumably the employees who remain are more skilled and have more seniority. The average Education and Health Services worker, in contrast, now brings home $26,655 annually. This is an $89 raise over 2017, which was the lowest year on record.

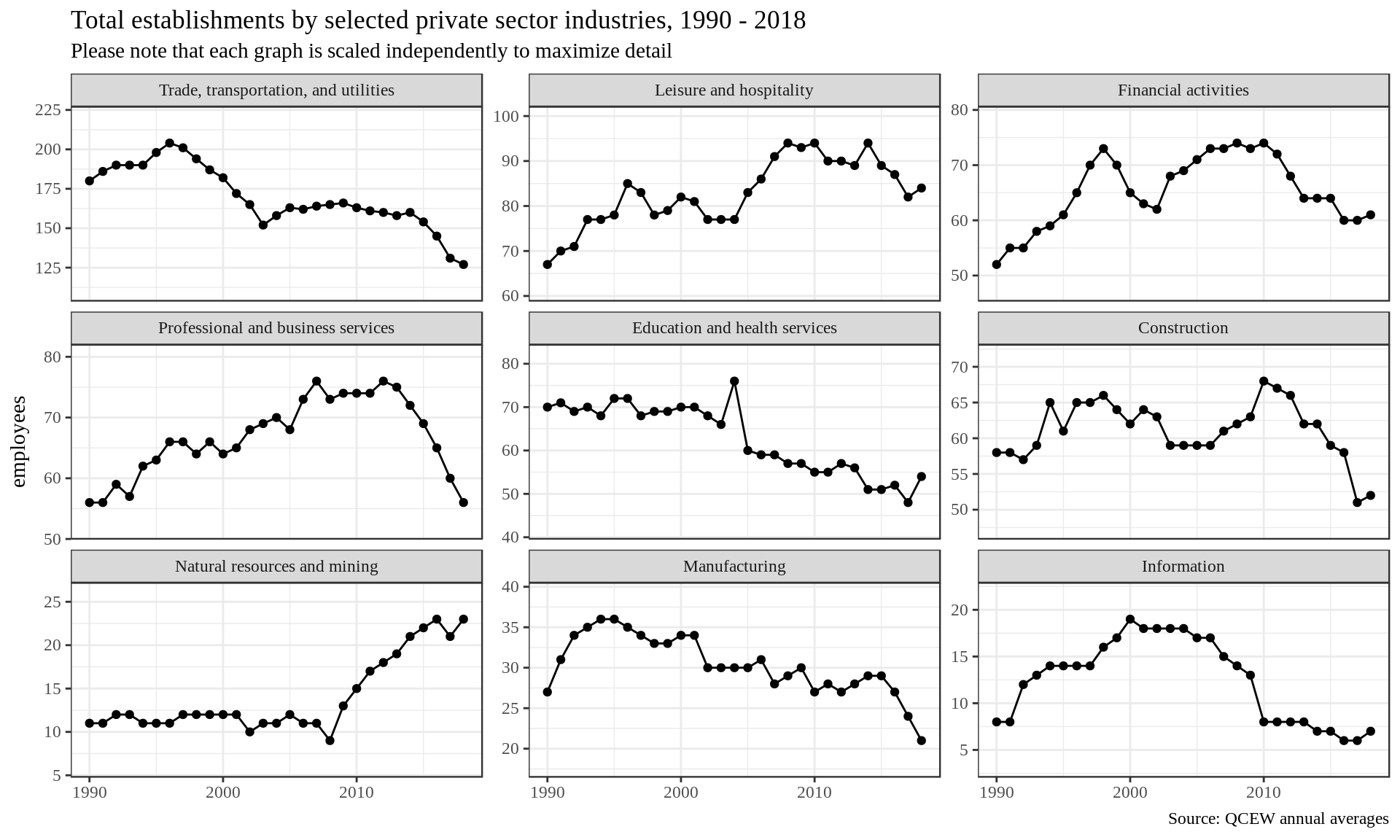

The total number of employers (or establishments) in McDonough County closely mirrors the region’s economic trajectory as a whole. After peaking around 750 in the late 1990s, it fell during the early 2000s. A modest recovery followed but was quickly ended by the Great Recession. The total number of establishments in the county fell from 713 in 2008 to 603 in 2018.

Here is the trend in each industry.

The economy today

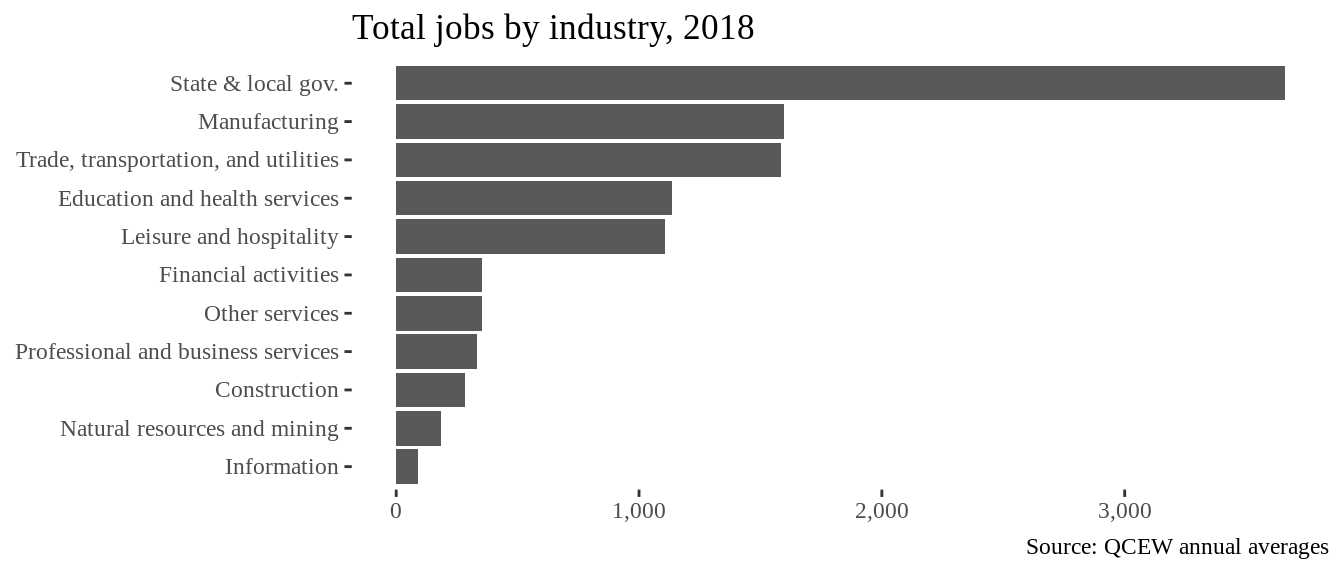

State and local government employees make up 34% of the county’s workforce. Trade, transportation, and utilities workers make up another 15%, as do manufacturing workers. They are followed by education and health services at 11% and leisure and hospitality at 10%. The remaining industries comprise 3% or less of all workers.

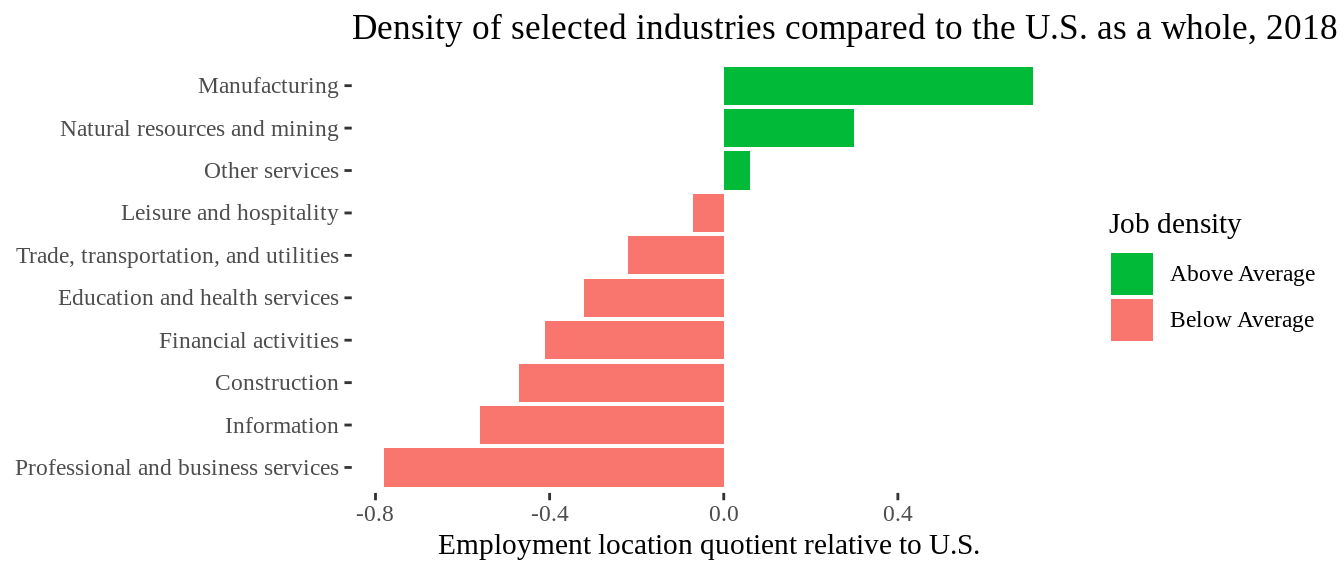

This graph shows how McDonough County’s job mix compares to the country as a whole. Industries with an “employment location quotient” above 0 (in green) are more common in McDonough than in the U.S. at large. The reverse is true of the industries with a location quotient below 0 (in pink).

McDonough County is most heavily relient on manufacturing and natural resources jobs. It has unusually low numbers of jobs in professional and business services, information industries, construction, financial activities, education and health services, and trade/transportation/utilities.

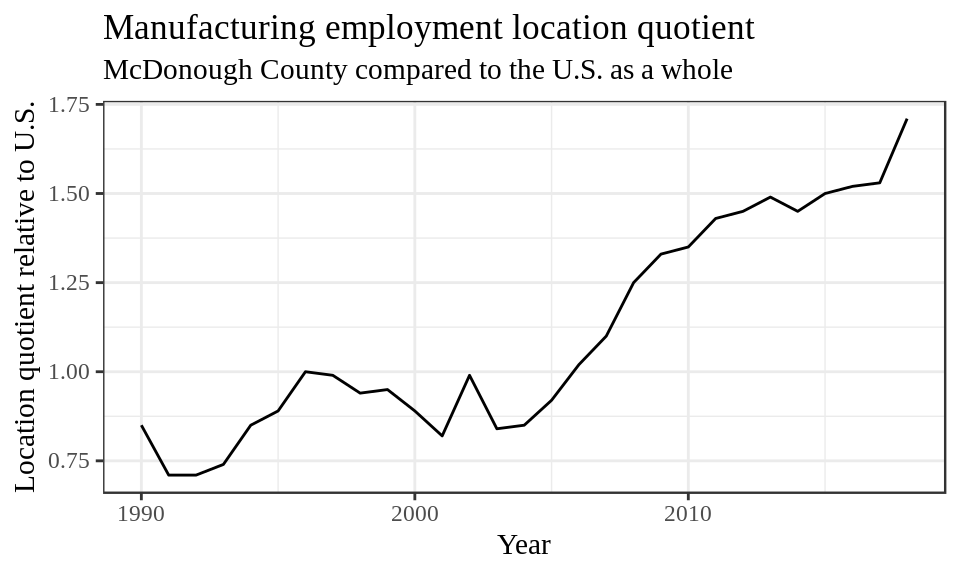

Even as the number of manufacturing jobs in the county has declined, McDonough’s relience on them has increased relative to the rest of the country. Even during the boom years of manufacturing in the late 1990s, McDonough County only relied on manufacturing jobs at about the same rate as the rest of the country. Now, the concentration of manufacturing jobs is 1.7 times that of the nation at large.

My dad left in 2003, about a year before Haegar Pottery’s Macomb factory shut down. The remaining factory in Dundee Illinois closed in 2016.↩

Incidentally, a study recently found this slaughterhouse to be the “worst-polluting meat processing plant in the U.S.”↩